1 What are GLMs?

1.1 Overview

General Linear models predict the value of a normally distributed response from a linear combination of predictor variables.

The Generalised Linear Model is an extension of the General Linear model for situations where the response variable does not follow the normal distribution. It can, instead, come from a large family of distributions known as the Exponential family which includes the normal, Poisson and binomial distributions. It generalises by allowing the linear model to be related to the response variable by a something we call a link function.

When you have a single explanatory variable, the General Linear model is:

\[\begin{equation} E(y_{i})=\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}X1_{i} \tag{1.1} \end{equation}\]

Where:

-

\(y\) is the response variable and \(X1\) is the explanatory variable.

- \(i\) is the index so \(X1_{i}\) is the \(i\)th value of \(X1\)

- \(E(y_{i})\) is the expected value of \(y\) for the \(i\)th value of \(X1\).

- \(\beta_{0}\) and \(\beta_{1}\) are the coefficients in the model.

And that for the Generalised Linear Model is: \[\begin{equation} function(E(y_{i}))=\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}X1_{i} \tag{1.2} \end{equation}\]

Where:

- \(function()\) is the link function

The link function is a transformation applied to the expected value of the response to link it to the explanatory variables.

If you measured the response for a particular value of \(x\) very many times there would be some distribution of those responses. Instead of that distribution having to be normal, it can come from a different distribution such as the Poisson or Binomial distributions. As a consequence, the residuals also come from that distribution. The fact that the residuals can follow a distribution other than normal also means the the variance no longer has to be homogeneous but can change for the values of x.

You can see that the two model equations are similar in structure. This is with good reason - you can think of the general linear model as a special case of generalised linear model when no transformation to the expected value, \(E(y_{i})\), is required.

A very important difference between the general linear model (applied with lm()) and the generalised linear model (applied with glm()) is that the estimates of the coefficients are given on the scale of the link function. You cannot just read the predicted response at \(x=0\) from \(\beta_{0}\) - you have to invert the link function to express the coefficients in terms of the response.

Response variables that are binary or counts can be analysed with GLMs. The estimated coefficients in GLMs have been transformed by a link function. The inverse of the link function has to be applied to them to understand them in terms of the response.

1.2 Model fitting

Another important difference between these models is in the measure of fit and the test on that measure of fit. The parameters of General linear models are chosen to minimise the sum of the squared residuals and use \(R^2\), the proportion of variance explained. A variance ratio test, the F-test, is used to determine if the proportion of variance explained is significant.

In GLMS we maximise the log-likelihood of our model (\(l\)) to choose our parameter values. This is known as maximum likelihood estimation. The measure of fit used in GLMs is deviance where deviance is \(-2l\). Low deviance means a good fit and high deviance a worse fit. Thus maximum likelihood estimation can be thought of as minimising deviance. The test again compares the deviance of predictions from the model with deviance in an intercept only model. This deviance in predictions from the intercept alone is called the Null deviance.

Instead of considering the size of the \(R^2\) we consider the reduction in deviance between the null model and the residual deviance (the deviance left over after the model fit). You can consider the residual deviance to play the same role as \(SSE\). The difference between the null model deviance and the residual deviance of the full model has a chi-squared distribution and the test of whether the model is good overall is a “chi-squared test of deviance” This is analogous to the way that general linear model uses the \(F\) variance ratio test.

GLMs maximise log-likelihood to choose coefficient values rather than minimising the sum of the squared residuals (\(SSE\)) as in general linear models. Residual deviance rather than \(SSE\) represents the unexplained variation in the response and Null deviance is analogous to total sums of squares. Model fit is tested with a chi-squared test of deviance rather than an \(F\) test of variance

The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is measure of fit that plays the same role in GLMs that adjusted \(R^2\) plays in the general linear model. It is trade-off between the goodness of fit of the model and the simplicity of the model. AIC values can also be determined for general linear models (but adjusted \(R^2\) cannot be calculated for GLMs).

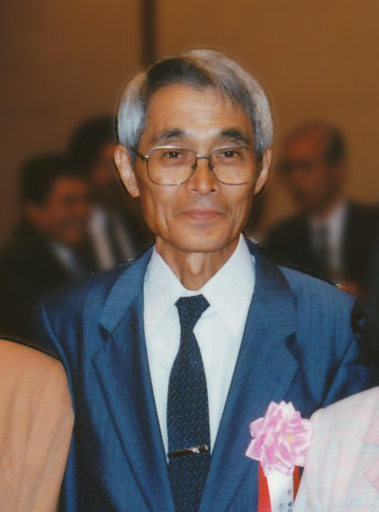

Figure 1.1: Hirotugu Akaike. By The Institute of Statistical Mathematics - The Institute of Statistical Mathematics, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64389664

1.3 Types of GLM

Poisson GLMs are used when our response is a count. They are also known as GLMs with Poisson errors or Poisson regression. The link function is the natural logarithm, \(ln\), a function you probably know. This means the predictions are log counts and the coefficients have to be exponentiated using exp() to get predicted counts because exp() is the inverse of log().

In R, the log() function computes natural logarithms (i.e., logs to the base \(e\) by default.

Binomial GLMs are used when our response is binary, a zero or one, or a proportion. For example, the response could be died (0) or survived (1), absent (0) or present (1) or right-handed (0) or left-handed (1). Binomial GLMs are also known as GLMs with binomial errors, binomial regression or logistic regression. The link function is \(logit\), a function you may not have heard of before. The predictions are “log-odds.” An “odds” is one probability divided by another. The coefficients have to be exponentiated using exp() and interpreted as odds. Often the easiest way to understand the predictions is to use the predict() function to get predictions on the scale of the response. If the binomial variable is died (0) or survived(1) these will be probabilities of survival.

Poisson GLMs are used when our response is a count and the estimates are log counts. Binomial GLMs are used when our response is binary and the estimates a log-odds. The predict() is especially useful in understanding binomial GLMs.

1.4 More than one explanatory variable

When you have more than one explanatory variable these are given as \(X2\), \(X3\) and so on up to the \(p\)th explanatory variable. Each explanatory variable has its own \(\beta\) coefficient.

The general form of the model is: \[\begin{equation} function(E(y_{i}))=\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}X1_{i}+\beta_{2}X2_{i}+...+\beta_{p}Xp_{i} \tag{1.3} \end{equation}\]

1.5 Generalised linear models in R

1.5.1 Building and viewing

Poisson and binomial generalised linear models (and others) can be carried out with the glm() function in R. It uses the same method, response ~ explanatory for specifying the model that other functions, including lm(), use. However, you also have to specify the type of GLM using the family argument:

When you have one explanatory variable the command is:

glm(data = dataframe, response ~ explanatory, family = distribution(link = linkfunction))

For a Poisson GLM this is:

glm(data = dataframe, response ~ explanatory, family = poisson(link = log))

For a binomial GLM this is:

glm(data = dataframe, response ~ explanatory, family = binomial(link = “logit”))

The model formula can be developed in the same way we’ve seen previously. When you have two explanatory variable we add the second explanatory variable to the formula using a + or a *. The command is:

glm(data = dataframe, response ~ explanatory1 + explanatory2, family = distribution(link = linkfunction))

or

glm(data = dataframe, response ~ explanatory1 * explanatory2, family = distribution(link = linkfunction))

A model with explanatory1 + explanatory2 considers the effects of the two variables independently. A model with explanatory1 * explanatory2 considers the effects of the two variables and any interaction between them.

We usually assign the output of glm() commands to an object and view it with summary(). The typical workflow would be:

mod <- glm(data = dataframe, response ~ explanatory, family = distribution(link = linkfunction))

summary(mod)

glm() can be used to perform tests using the Generalised Linear Model including Poisson and Binomial regression. The type of GLM needs to be specified.

Elements of the glm() object include the estimated coefficients can be accessed with mod$coeffients.

1.5.2 Getting predictions

mod$fitted.values gives the predicted values for the explanatory variable values actually used in the experiment, i.e., there is a prediction for each row of data. These are given on the scale of the response. This means they will be predicted counts for Poisson GLMs and predicted probabilities for Binomial GLMs.

1.5.3 Tests of the model

With an lm() you get an F variance ratio test of the model over all when you view a summary. It answers the question “does the model explain a significant amount of the variation in the response relative to the response mean?”

With a glm() you do not get a test of the model over all when you view a summary. You have to ask for a chi-squared test of deviance. It answers the question “does the model significantly decrease the deviance relative to the response mean?”

anova(mod, test = “Chisq”)

To get predictions for a different set of values you need to make a dataframe of the different set of values and use the predict() function. When using the predict() function we have to specify that we want our predictions on the scale of the response rather than the scale of the link function using the type argument.

The typical workflow would be:

predict_for <- data.frame(explanatory = values)

predict_for$pred <- predict(mod, newdata = predict_for, type = “response”)