install.packages("tidyverse")

install.packages("readxl")6 First Steps in RStudio

You are reading a work in progress. This page is a first draft but should be readable.

This chapter starts by explaining what R and RStudio are and how you can install them on your own machine. We introduce you to working in RStudio, changing its appearance to suit you and to the key things you need to know about R.

6.1 What are R and Rstudio?

6.1.1 What is R?

R is a programming language and environment for statistical computing and graphics which is free and open source. It is widely used in industry and academia. It is what is known as a “domain-specific” language meaning that it is designed especially for doing data analysis and visualisation rather than a “general-purpose” programming language like Python and C++. It makes doing the sorts of things that bioscientists do a bit easier than in a general purpose-language.

6.1.2 What is RStudio?

RStudio is what is known as an “integrated development environment” (IDE) for R made by Posit. IDEs have features that make it easier to do coding like syntax highlighting, code completion and viewers for files, code objects, packages and plots. You don’t have to use RStudio to use R but it is very helpful.

6.1.3 Why is it better to use R than Excel, googlesheets or some other spreadsheet program?

Spreadsheet programs are not statistical packages so although you can carry out some analysis tasks in them they are limited, get things wrong (known about since 1994) and teach you bad data habits. Spreadsheets encourage you to do things that are going to make analysis difficult.

6.2 Installing R and Rstudio

You will need to install both R and RStudio to use them on your own machine. Installation is normally straightforward but you can follow a tutorial

6.2.1 Installing R

Go to https://cloud.r-project.org/ and download the “Precompiled binary distributions of the base system and contributed packages” appropriate for your machine.

6.2.1.1 For Windows

Click “Download R for Windows”, then “base”, then “Download R 4.#.# for Windows”. This will download an .exe file. Once downloaded, open (double click) that file to start the installation.

6.2.1.2 For Mac

Click “Download R for (Mac) OS X”, then “R-4.#.#.pkg” to download the installer. Run the installer to complete installation.

6.2.1.3 For Linux

Click “Download R for Linux”. Instructions on installing are given for Debian, Redhat, Suse and Ubuntu distributions. Where there is a choice, install both r-base and r-base-dev.

6.2.2 Installing R Studio

6.3 Packages

TODO some text

Install tidyverse:

6.4 Introduction to RStudio

In this section we will introduce you to working in RStudio. We will explain the windows that you see when you first open RStudio and how to change its appearance to suit you. Then we will see how we use R as a calculator and how assign values to R objects.

6.4.1 Changing the appearance

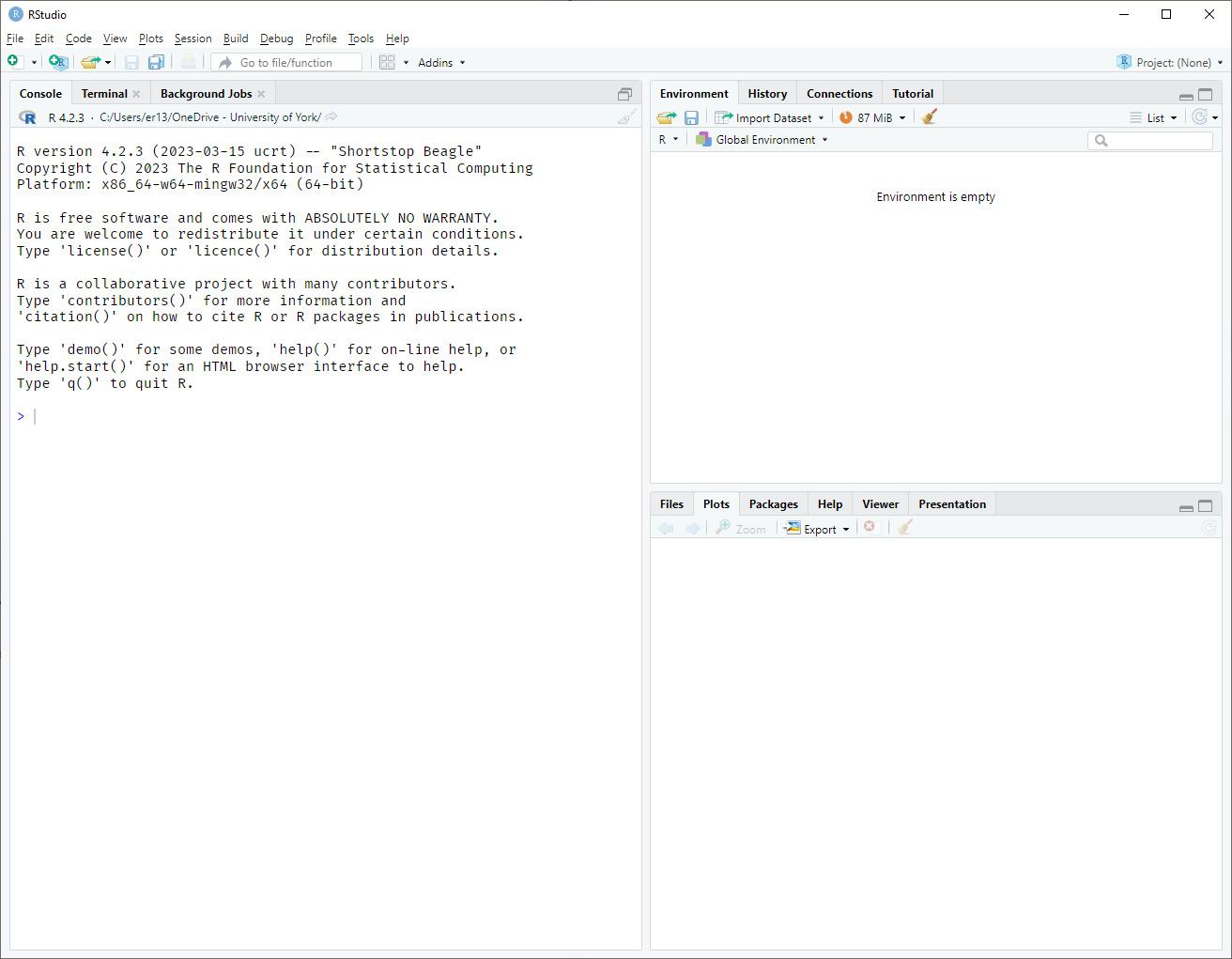

When you first open RStudio it will display three panes and have a white background Figure 6.1

We will talk more about these three panes soon but first, let’s get into character - the character of a programmer! You might have noticed that people comfortable around computers are often using dark backgrounds. A dark background reduces eye strain and often makes “code syntax” more obvious making it faster to learn and understand at a glance. Code syntax is the set of rules that define what the various combinations of symbols mean. It takes time to learn these rules and you will learn best by repeated exposure to writing, reading and copying code. You have done this before when you learned your first spoken language. All languages have syntax rules governing the order of words and we rarely think about these consciously, instead relying on what sounds and looks right. And what sounds and looks right grows out repeated exposure. For example, 35% of languages, including English, Chinese, Yoruba and Polish use the Subject-Verb-Object syntax rule:

- English: Emma likes R

- Chinese: 艾玛喜欢R Emma xǐhuān R

- Yoruba: Emma fẹran R

- Polish: Emma lubi R

and 40% use Subject-Object-Verb including Turkish and Korean

- Turkish: Emma R’yi seviyor

- Korean: 엠마는 R을 좋아한다 emmaneun Reul joh-ahanda

You learned this rule in your language very early, long before you were conscious of it, just by being exposed to it frequently. In this book I try to tell you the syntax rules, but you will learn most from looking at, and copying code. Because of this, it is well worth tinkering with the appearance of RStudio to see what Editor theme makes code elements most obvious to you.

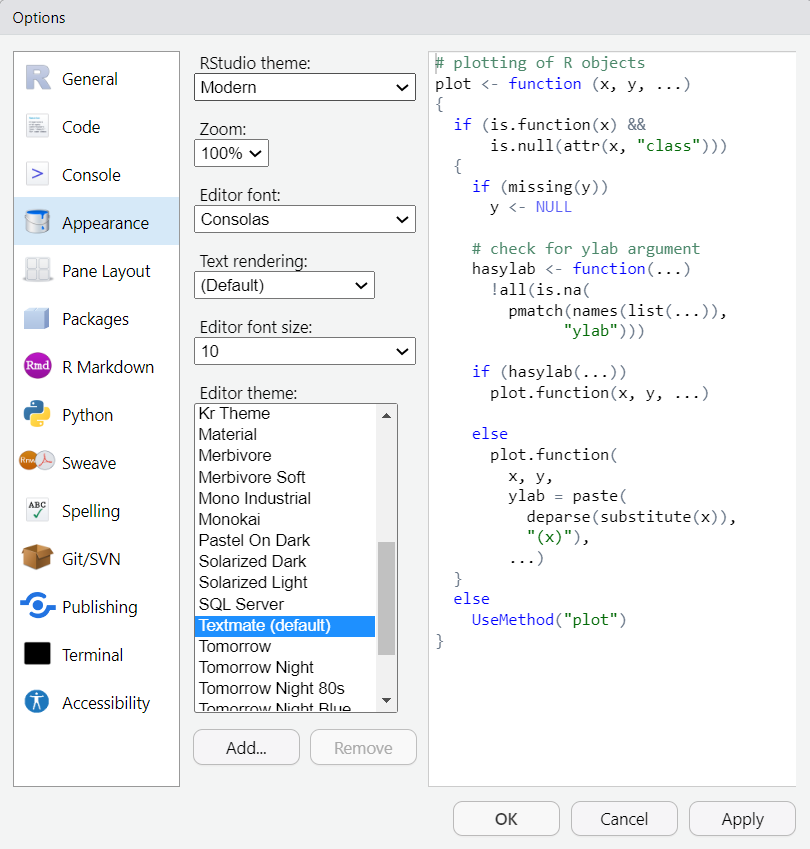

There is a tool bar at the top of RStudio. Choose the Tools option and then Global options. This will open a window where many options can be changed Figure 6.2.

Go to the Appearance Options and choose and Editor theme you like, followed by OK.

The default theme is Textmate. You will notice that all the Editor themes have syntax highlighting so that keywords, variable names, operators, etc are coloured but some themes have stronger contrasts than others. For beginners, I recommend Vibrant Ink, Chaos or Merbivore rather than Dreamweaver or Gob which have little contrast between some elements. However, individuals differ so experiment for yourself. I tend to vary between Solarised light and dark.

You can also turn one Screen Reader Support in the Accessibility Options in Tools | Global Options.

Back to the Panes. You should be looking at three windows: One on the left and two on the right1.

The window on the left, labelled Console, is where R commands are executed. In a moment we will start by typing commands in this window. Over on the right hand side, at the top, have several tabs, with the Environment tab showing. This is where all the objects and data that you create will be listed. Behind the Environment tab is the History and later you will be able to view this to see a history of all your commands.

On the bottom right hand side, we have a tab called Plots which is where your plots will go, a tab called Files which is a file explorer just like Windows Explorer or Mac Finder, and a Packages tab where you can see all the packages that are installed. The Packages tab also provides a way to install additional packages. The Help tab has access to all the manual pages.

Right, let’s start coding!

6.4.2 Your first piece of code

We can use R just like a calculator. Put your cursor after the > in the Console, type 3 + 4 and ↵ Enter to send that command:

3+4

## [1] 7The > is called the “prompt”. You do not have to type it, it tells you that R is ready for input.

Where I’ve written 3+4, I have no spaces. However, you can have spaces, and in fact, it’s good practice to use spaces around your operators because it makes your code easier to read. So a better way of writing this would be:

3 + 4

## [1] 7In the output we have the number 7, which, obviously, is the answer. From now on, you should assume commands typed at the console should be followed by ↵ Enter to send them.

The one in parentheses, [1], is an index. It is telling you that the 7 is the first element of the output. We can see this more clear if we create something with more output. For example, 50:100 will print the numbers from 50 to 100.

50:100

## [1] 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68

## [20] 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87

## [39] 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100The numbers in the square parentheses at the beginning of the line give you the index of the first element in the line. R is telling you where you are in the output.

6.4.3 Assigning variables

Very often we want to keep input values or output for future use. We do this with ‘assignment’ An assignment is a statement in programming that is used to set a value to a variable name. In R, the operator used to do assignment is <-. It assigns the value on the right-hand to the value on the left-hand side.

To assign the value 3 to x we do:

x <- 3and ↵ Enter to send that command.

The assignment operator is made of two characters, the < and the - and there is a keyboard short cut: Alt+- (windows) or Option+- (Mac). Using the shortcut means you’ll automatically get spaces. You won’t see any output when the command has been executed because there is no output. However, you will see x listed under Values in the Environment tab (top right).

Your turn! Assign the value of 4 to a variable called y:

Code

y <- 4Check you can see y listed in the Environment tab.

Type x and ↵ Enter to print the contents of x in the console:

x

## [1] 3We can use these values in calculations just like we could in in maths and algebra.

x + y

## [1] 7We get the output of 7 just as we expect. Suppose we make a mistake when typing, for example, accidentally pressing the u button instead of the y button:

x + u

## Error: object 'u' not foundWe get an error. We will probably see this error quite often - it means we have tried to use a variable that is not in our Environment. So when you get that error, have a quick look up at your environment2.

We made a typo and will want to try again. We usefully have access to all the commands that previously entered when we use the ↑ Up Arrow. This is known as command recall. Pressing the ↑ Up Arrow once recalls the last command; pressing it twice recalls the command before the last one and so on.

Recall the x + u command (you may need to use the ↓ Down Arrow to get back to get it) and use the Back space key to remove the u and then add a y.

A lot of what we type is going to be wrong - that is not because you are a beginner, it is same for everybody! On the whole, you type it wrong until you get it right and then you move to the next part. This means you are going to have to access your previous commands often. The History - behind the Environment tab - contains everything you can see with the ↑ Up Arrow. You can imagine that as you increase the number of commands you run in a session, having access the this record of everything you did is useful. However, the thing about the history is, that it has everything you typed, including all the wrong things!

What we really want is a record of everything we did that was right! This is why we use scripts instead of typing directly into the console.

6.4.4 Using Scripts

An R script is a plain text file with a .R extension and containing R code. Instead of typing into the console, we normally type into a script and then send the commands to the console when we are ready to run them. Then if we’ve made any mistakes, we just correct our script and by the end of the session, it contains a record of everything we typed that worked.

You have several options open a new script:

- button: Green circle with a white cross, top left and choose R Script

- menu: File | New File | R Script

- keyboard shortcut: Ctrl+Shift+N (Windows) / Shift+Command+N (Mac)

Open a script and add the two assignments to it:

x <- 3

y <- 4To send the first line to the console, we place our cursor on the line (anywhere) and press Ctrl-Enter (Windows) / Command-Return. That line will be executed in the console and in the script, our cursor will jump to the next line. Now, send the second command to the console in the same way.

From this point forward, you should assume commands should be typed into the script and sent to the console.

Add the incorrect command attempting to sum the two variables:

x + u

## Error: object 'u' not foundTo correct this, we do not add another line to the script but instead edit the existing command:

x + y

## [1] 7In addition to making it easy to keep a record of your work, scripts have another big advantage, you can include ‘comments’ - pieces of text that describe what the code is doing. Comments are indicated with a # in front of them. You can write anything you like after a # and R will recognise that it is not code and doesn’t need to be run.

# This script performs the sum of two values

x <- 3 # can be altered

y <- 4 # can be altered

# perform sum

x + y

## [1] 7The comments should be highlighted in a different colour than the code. They will be italic in some Editor themes.

You have several options save a script:

- button: use the floppy disc icon

- menu: File | Save

- keyboard shortcut: Ctrl+S (Windows) / Command+S (Mac)

You could use a name like test1.R - note the .R extension wil be added automatically.

6.4.5 Other types of file in RStudio

-

.Rscript code but not the objects. You always want to save this -

.Rdataalso known as the workspace or session, the objects, but not the code. You usually do not want to save this. Some exceptions e.g., if it takes quite a long time to run the commands. - text files

6.4.6 Changing some defaults to make life easier

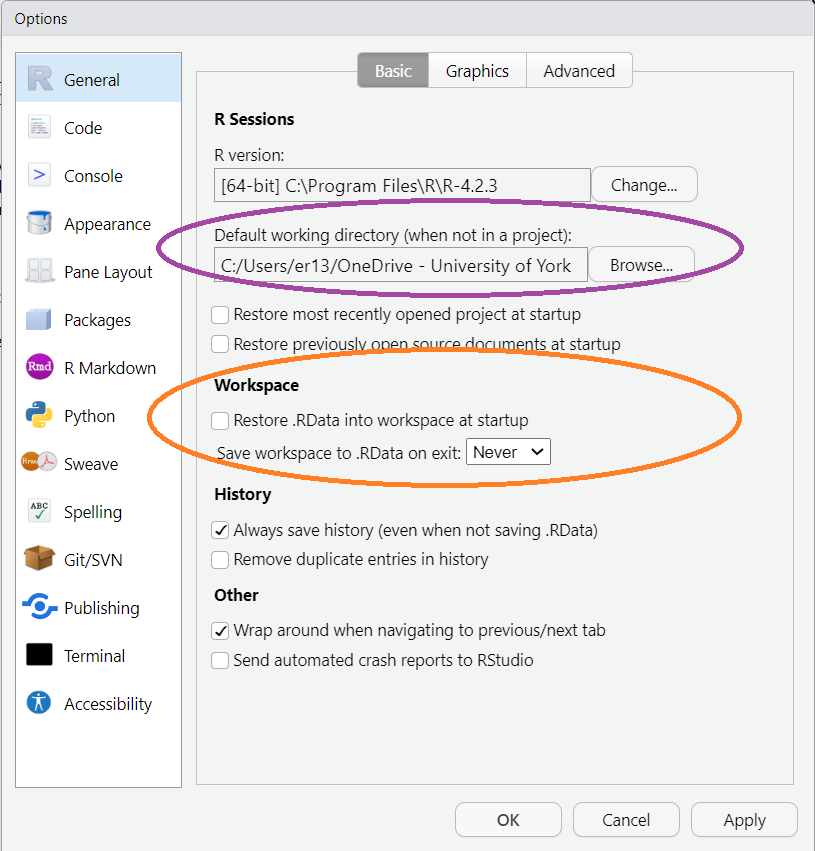

I recommend changing some of the default settings to make your life a little easier. Go back into the Global Options window with Tools | Global Options. The top tab is General Figure 6.3.

First, we will set our default working directory. Under ‘Default working directory (when not in a project3):’ click Browse and navigate to a through your file system to a folder where you want to work. You may want to create a folder specifically for studying this book.

Second, we will change the Workspace options. Turn off ‘Restore .RData into workspace at startup’ and change ‘Save workspace to .RData on exit’ to ‘Never’. These options mean R will start up clean each time.

6.5 Recap of RStudio anatomy

This figure (see Figure 6.44) summarises shows what each of the four RStudio panes and what they are used for to summarise much of what we have covered so far.

6.6 Data types and structures in R

In this section, we are going to introduce you to some of R’s data types and structures. We won’t be covering all of them now, just those you are going to use often in this part of the book. These are numerics (numbers), characters, ‘logicals’, vectors and dataframes. We can do a lot with just these. We will also cover using functions.

We are going to consider

types of value also known as data types

functions

data structures

6.6.1 Data types

This refers to the type of value that something is. They might be numerics or characters or ‘logical’ (either true of false). We assign a number, like the value of 23 to a variable called x like this:

x <- 23

x

## [1] 23We do not need to use quotes for numbers but we do need to use them for characters and can assign the word banana to the variable a like this:

a <- "banana"

a

## [1] "banana"Quotes are needed because otherwise R wouldn’t know whether you were referring to a value or a existing object called banana. This is also why you can’t have variable name like 14 - R would not be able to tell the difference between the number 14 and an object named 14 since numbers and objects don’t need quotes.

Anything composed of non-numeric characters, including single characters, need to have quotes around it. You can even force a number to be a character by putting quotes around it:

b <- "23"

b

## [1] "23"Notice that things inside quotes appear in a different colour (the colour will depend on the Editor theme you choose). This will help you identify when you have forgotten some closing quotes5:

a <- "banana

x <- 23Although the data type is ‘character’ we often use the term ‘string’ for collections - strings - of characters

We also have special values called ‘logicals’ which take a value of either TRUE or FALSE.

c <- TRUE

c

## [1] TRUEAlthough TRUE is a word, R recognises it as special word. It appears in a different colour and no quotes are needed. This is the same for FALSE.

c <- FALSE

c

## [1] FALSEAs you type FALSE, the colour changes as it recognises the special word FALSE. Try to pay attention to the editor theme’s colouring - it is trying to help you!

6.6.2 Functions

The aim of this section is to help you understand the logic of using a function. Functions have a name and then a set of parentheses. The function name minimally explains what the function does. Inside the parentheses are ‘arguments’ - the pieces of information you give to the function. When coding, we often talk about passing arguments to functions and calling functions. A simple function call looks like this:

function_name(argument)A function can take zero to many arguments. Where you give several arguments, they are separated by commas:

function_name(argument1, argument2, argument3, ...)The first function you are going to use is str() which gives the structure of an object:

str(x)

## num 23It’s telling me that x is a number and contains 23.

Your turn! Use str() on b:

Code

str(b)

## chr "23"str() is a function I use a lot to check what sort of R object I have.

We must give str() at least one argument, the object we want the structure of, but additional arguments are also possible. Later we will discover how to find out and use a function’s arguments.

So far we our objects have consisted of a single thing but usually we have several bits of data that we want to collect together into a data structure.

6.6.3 Data structures: vectors

Imagine we have the ages of six people. Since all the numbers are ages, we would want to keep them together. The minimal data structure is called a vector. We can create a vector, which collects together several numbers using a function, c(). This is one of only a few functions in R with a single-letter name. Because it has a single letter, sometimes people get confused about it but we can tell it is a function because it has a set of parentheses.

To create a vector called ages of several numbers we use

ages <- c(23, 42, 7, 9, 54, 12)Type ages and run if you want to print the contents to the console:

ages

## [1] 23 42 7 9 54 12Using str() on ages

str(ages)

## num [1:6] 23 42 7 9 54 12tells us we have numbers with the indices of 1 to 6.

We can also create a vector of strings. Suppose we have names to go with the ages.

names <- c("Rowan", "Aang", "Zain", "Charlie", "Jules", "Efe")RStudio has a super useful feature for putting items in quotes, brackets or parentheses if you initially forget them: If you select something and type the opening element, that thing will be surrounded rather than over written. For example, if you had written:

names <- Rowan, Aang, Zain, Charlie, Jules, EfeSelect one of the names and then type an opening quote - you should see the name is then surrounded by quotes rather than overwritten. You can repeat this process for all the names (note that double clicking on the name will select it). Selecting the whole list and typing an opening parenthesis will put the whole list in parentheses. This is a feature you get to love so much and use so often that other programs will annoy you when you overwrite something you meant to quote!

So we can also have vectors of logical values. For example, we might have a vector that indicates that Rowan, Aang and Charlie like chocolate, but Zain, Jules and Efe do not:

chocolate <- c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, FALSE)Remember, because TRUE and FALSE are special words so we do not need quote them.

6.6.4 Indexing vectors

You might be wondering how to get a single element out of a vector if typing the vector’s name prints the entire vector. This is by ‘indexing’. An index is a number from 16 to the length of a vector which gives the position in the vector and is denoted by square brackets. For example, to pull out the second element of ages:

ages[2]

## [1] 42Your turn! Print the last element of names:

Code

names[6]

## [1] "Efe"We an extract more than one element by giving more than one index. If the indices are adjacent like 3rd, 4th and 5th, we have use the colon:

names[3:5]

## [1] "Zain" "Charlie" "Jules"If the indices are not adjacent, like 2 and 6 with need to combine them with c():

names[c(2, 6)]

## [1] "Aang" "Efe"We can also use a logical vector to extract elements. Suppose you want to extract the names and ages of the people who like chocolate:

names[chocolate]

## [1] "Rowan" "Aang" "Charlie"

ages[chocolate]

## [1] 23 42 9At each of the indices in chocolate that contain TRUE, the name and age are returned.

6.6.5 Changing the defaults for a function

The functions we have used so far, c() and str() have worked without us having to change default behaviour. For example, if we want to calculate the mean age of our people we can use the mean() function in default form:

mean(ages)

## [1] 24.5Imagine Charlie would like their age removed from the dataset or that we never knew their age. We would not want a vector containing just five elements because the ages would not match the people in the same position in the vector. Instead, we would have a missing value at that position. Missing values are NA (not applicable) in R and NA is another special word, like TRUE and FALSE, that doesn’t need quotes. We can set Charlie’s age to NA using indexing:

ages[names == "Charlie"] <- NA

ages

## [1] 23 42 7 NA 54 12The == means “is equal to” and the result of names == "Charlie" is a vector of logicals: FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE. This means ages[names == "Charlie"] references the age in ages at the index of Charlie in names

If we now try to calculate the mean age:

mean(ages)

## [1] NAWe get an NA! What we really want is an average of the ages we do have. The mean() function has an argument that allows you to cope with that situation called na.rm. By default, na.rm is set to FALSE but we can set it to TRUE using

mean(ages, na.rm = TRUE)

## [1] 27.66.6.6 Data structures: dataframes

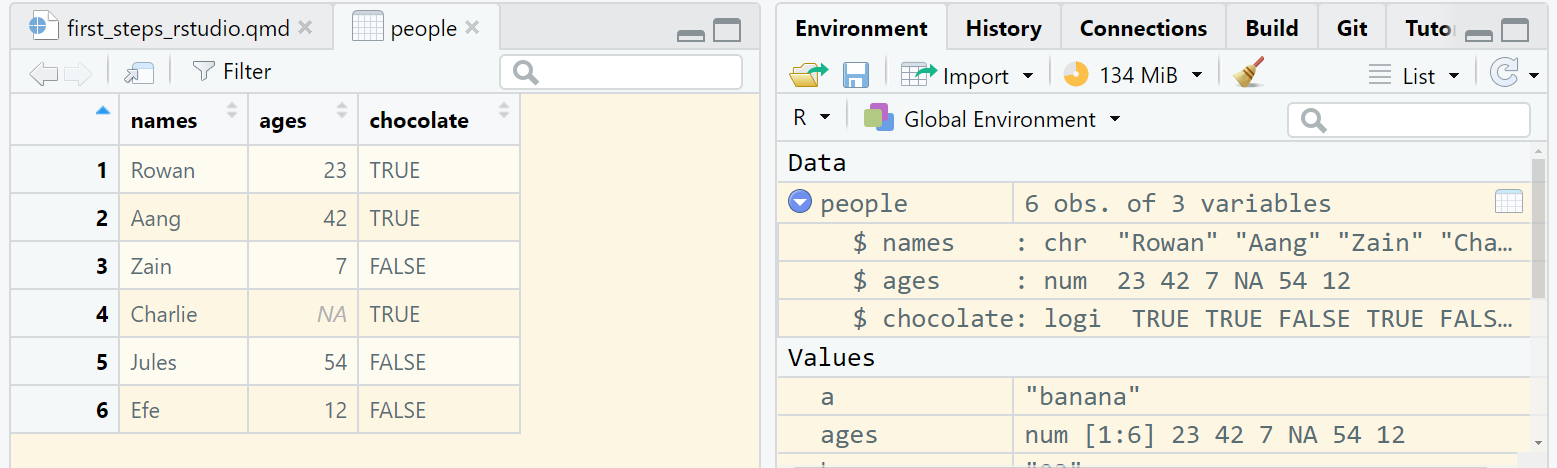

We have three vectors, names, ages and chocolate which are all part of the same dataset. By far the most common way of organising data in R is within a “dataframe”. A dataframe, has rows and columns: each column represents a variable and each row represents a case. To make a dataframe using our three vectors we use:

people <- data.frame(names, ages, chocolate)You will see people listed in the Global environment under Data. To open a spreadsheet-like view of the dataframe click its name in the Global Environment Figure 6.5

6.7 Summary

TODO

If this is not a fresh install of RStudio, you might be looking at fours windows, two on the left and two on the right. That’s fine - we will al be using four shortly. For the time being, you might want to close the “Script” window using the small cross next to “Untitled1”.↩︎

When we are using scripts, it is very easy to write code but forget to run it. Very often when you see this error it will because you have written the code to create an object but forgotten to execute it.↩︎

We will find out what an RStudio Project is very soon. You will want to use a project for most of your work - they make everything a little easier.↩︎

You can zoom into this at the Direct link↩︎

RStudio makes it hard for you to forget closing quotes and parentheses because when you type an opening quote or parenthesis, it automatically adds its closing partner. When people are learning they are sometimes tempted to delete these so they can type what goes inside the quotes/parentheses and then manually add the closing partner. I strongly recommend you don’t not delete them. RStudio adds the closing character but it leaves your cursor in the right position to complete the contents.↩︎

We start counting from 1 in R. Most programming languages count from zero.↩︎