9 The logic of hyothesis testing

You are reading a work in progress. This page is compete but needs final proof reading.

9.1 What is Hypothesis testing?

Hypothesis testing is a statistical method that helps us draw conclusions about a population based on a sample. Since we usually can’t measure every individual in a population, we take a smaller sample and analyze it.

For example, suppose we want to know if babies born to mothers in poverty have lower birth weights than the national average. Measuring the birth weight of every baby in the country would be impossible, so we take a sample. However, even if poverty has no real effect, our sample’s average birth weight might be different from the national average just by chance. Hypothesis testing helps us determine whether this difference is real or just random variation.

9.2 Samples and populations

Before we dive deeper into hypothesis testing, let’s clarify two key terms:

- A population is the entire group we are interested in studying (e.g., all babies in a country).

- A sample is a smaller group selected from the population (e.g., a few hundred babies chosen for the study).

We use samples because studying an entire population is often impractical. The challenge is making sure our sample accurately represents the population.

9.3 Logic of hypothesis testing

The logic behind hypothesis testing follows these general steps:

- Formulating a “Null Hypothesis” denoted \(H_0\). The null hypothesis is what we expect to happen if nothing interesting is happening. It states that there is no difference between groups or no relationship between variables. In contrast, the “Alternative Hypothesis” (\(H_1\)) states that there is a significant difference between groups or a relationship between variables.

- Designing an experiment and/or collecting data to test the null hypothesis.

- Finding the probability (the p-value) of getting our experimental data, or data more extreme, if \(H_0\) is true.

- Deciding whether to reject or not reject the \(H_0\) based on that probability:

- If \(p ≤ 0.05\) we reject \(H_0\)

- If \(p > 0.05\) do not reject \(H_0\)

If the null hypothesis is rejected it means we have evidence that \(H_0\) is untrue and support for \(H_1\). If the null hypothesis is not rejected, it means there is insufficient evidence to support the alternative hypothesis. It is important to recognise that not rejecting the null hypothesis does not mean \(H_0\) is definitely true. It just means just that \(H_0\) cannot be discounted.

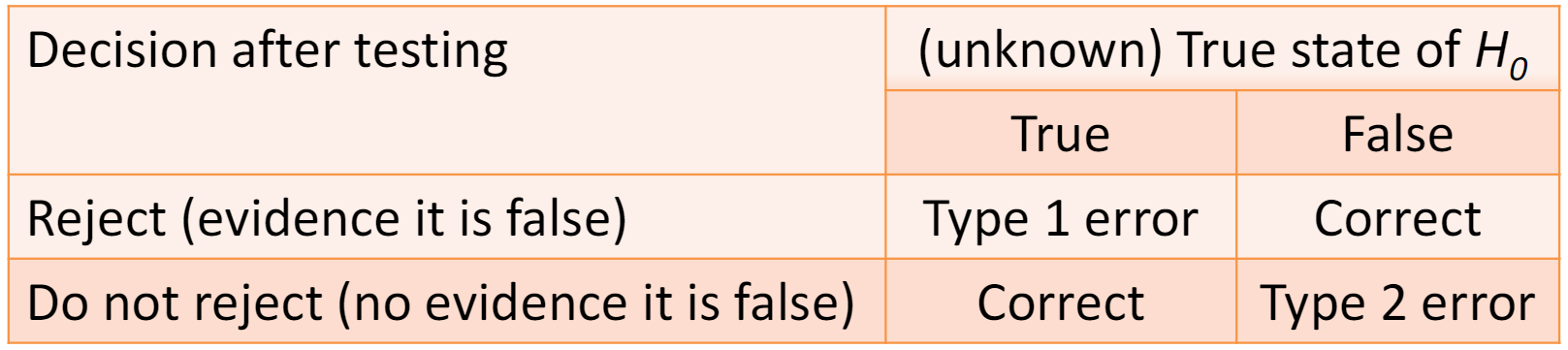

There is a real state to \(H_0\), that is, \(H_0\) is either true or it is not true. The statistical test has us decide whether to reject or not reject \(H_0\) based on the p-value. This means we can make mistakes when testing a hypothesis. These are called Type I and Type II errors.

9.3.1 Type I and type II errors

Type I and type II errors describe the cases when we make the wrong decision about the null hypothesis. These errors are inherent in the approach rather than mistakes you can prevent.

- A type I error occurs when we reject a null hypothesis that is true. This can be thought of as a false positive. It is a real error in that we have a real difference or effect. Since we use a probability of 0.05 to reject the null hypothesis, we will make a type I error 5% of the time.

- A type II error occurs when we do not reject a null hypothesis that is false. This is a false negative. It is not a real error in the sense that we only conclude we do not have enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

- If we reject a null hypothesis that is false we have not made an error.

- If we do not reject a null hypothesis that is true we have not made an error.

We can decrease our chance of making a type I error by reducing the the p-value required to reject the null hypothesis. However, this will increase our chance of making a type II error. We can decrease our chance of making a type II error by collecting enough data. The amount of data needed will depend on the the size of the effect relative to the random variation in the data.

9.4 Sampling distribution of the mean

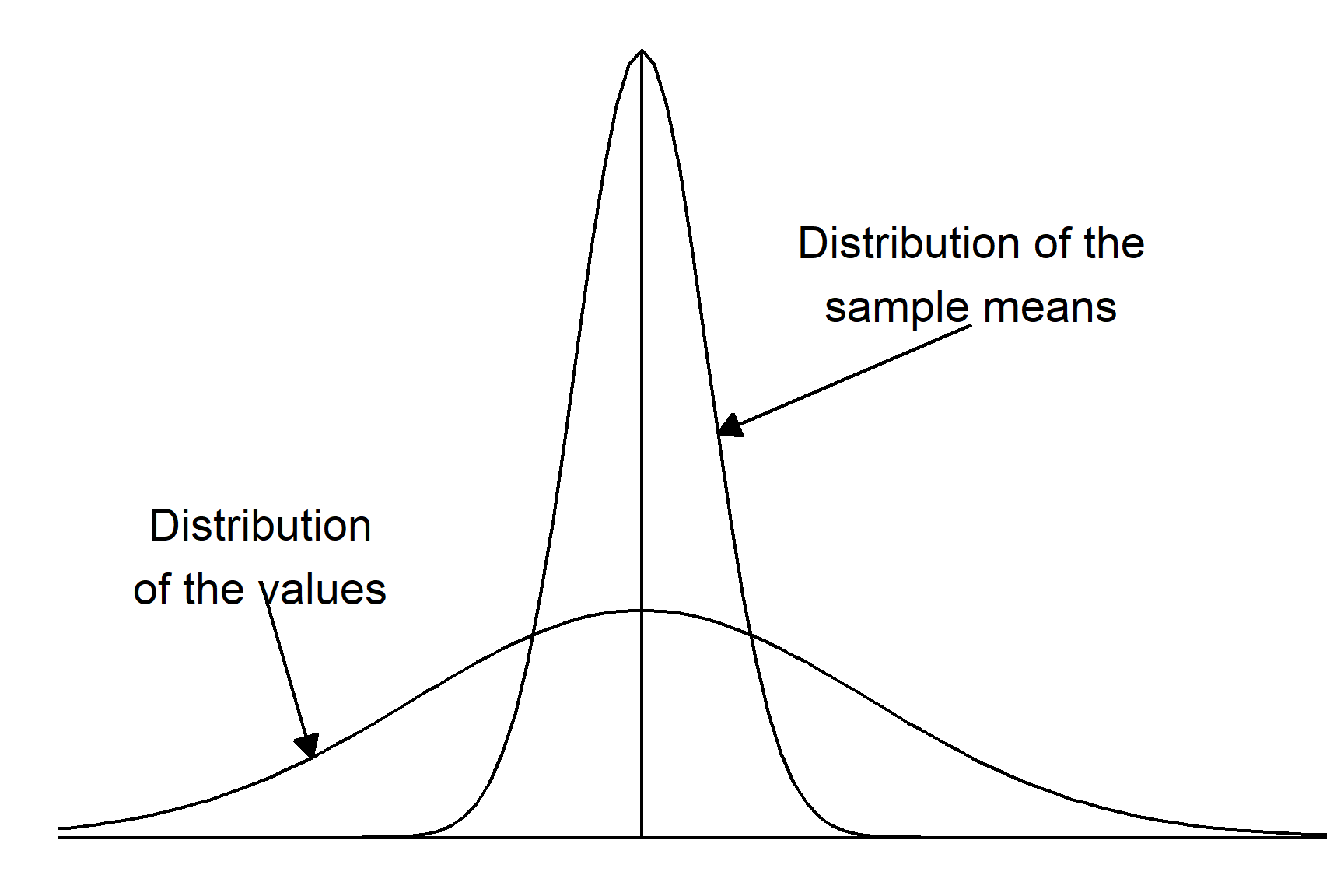

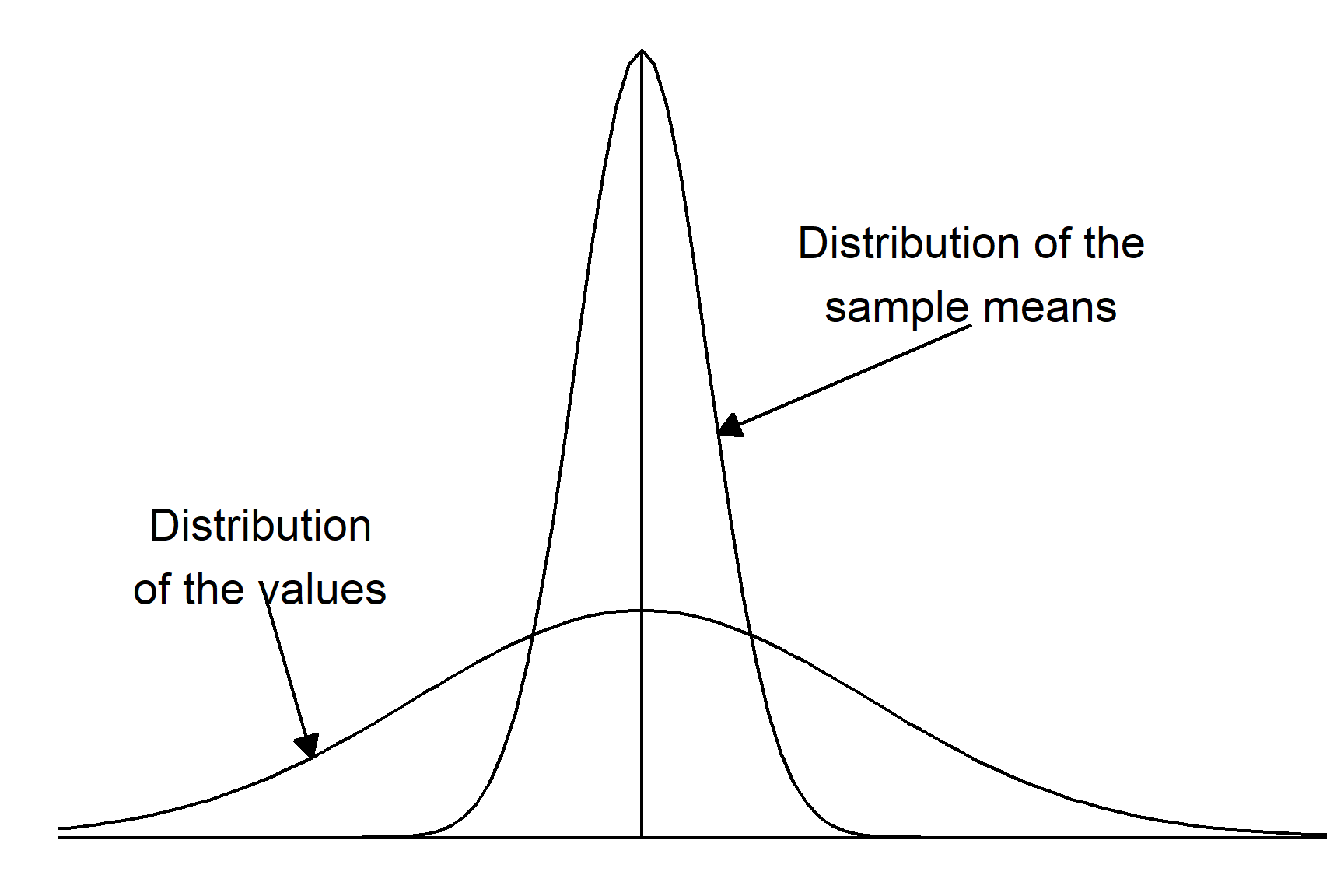

The sampling distribution of the mean is a fundamental concept in hypothesis testing and constructing confidence intervals. Parametric tests such as regression, two-sample tests and ANOVA (all applied with lm()) are based on the sampling distribution of the mean. It is a theoretical distribution that describes the distribution of the sample means if an infinite number of samples were taken.

The key characteristics of the sampling distribution of the mean are:

The mean of the sampling distribution of the mean is equal to the population mean

The standard deviation of the sampling distribution of the mean is known the standard error of the mean and is always smaller than the standard deviation of the values. There is a fixed relationship between the standard deviation of a sample or population and the standard error of the mean: \(s.e. = \frac{s.d.}{\sqrt{n}}\)

💡 Why does this matter? When we calculate a p-value, we’re really asking: “How likely is it to get a sample mean like ours (or more extreme) if \(H_0\) is true. This is why understanding the sampling distribution is so important - it helps us determine what results we should expect by random chance.

9.4.1 Example

Let’s work through this logic using an example.

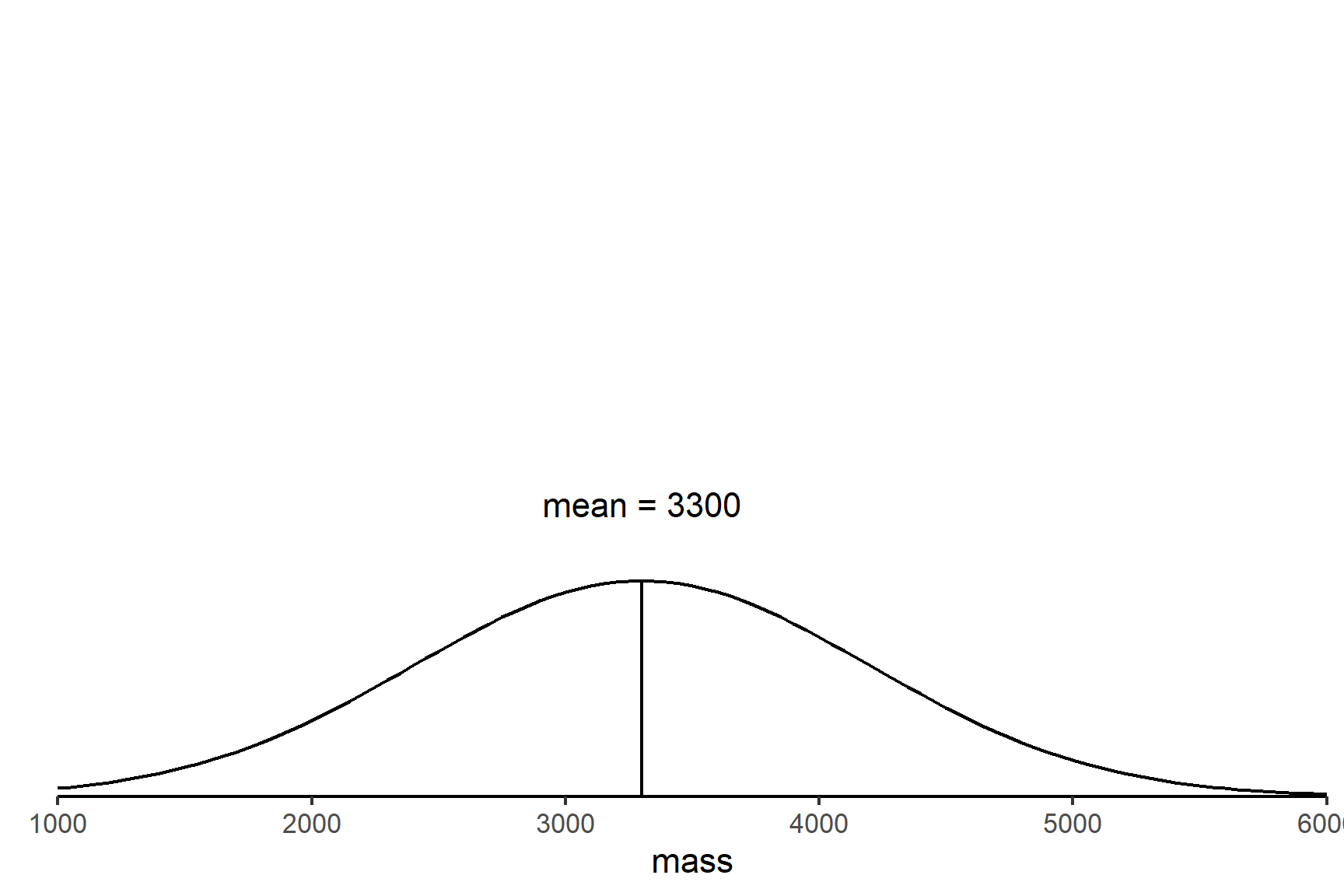

Question: National average birth weight is 3300 grams with an s.d. = 900 grams. Does maternal poverty influence birth weight?

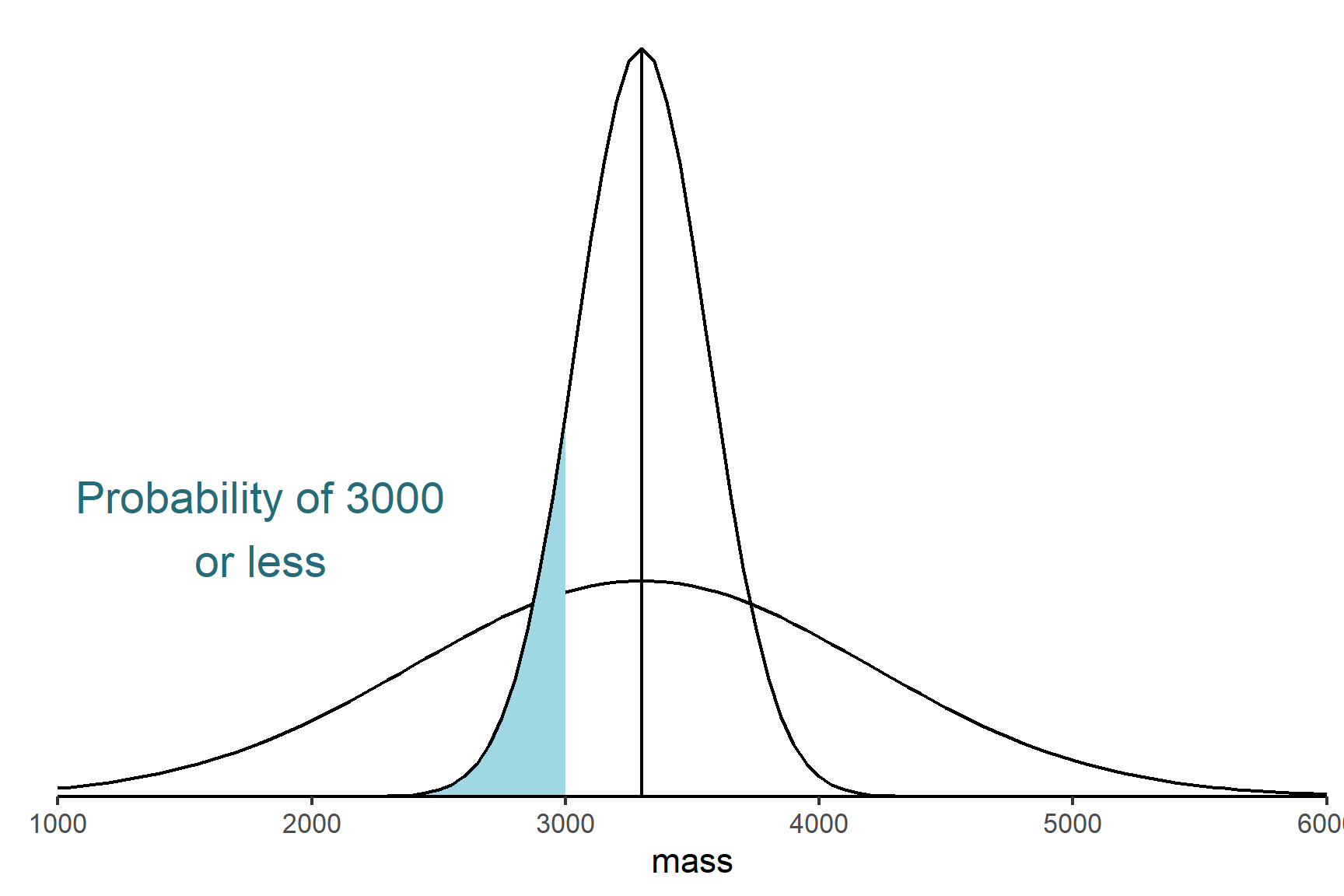

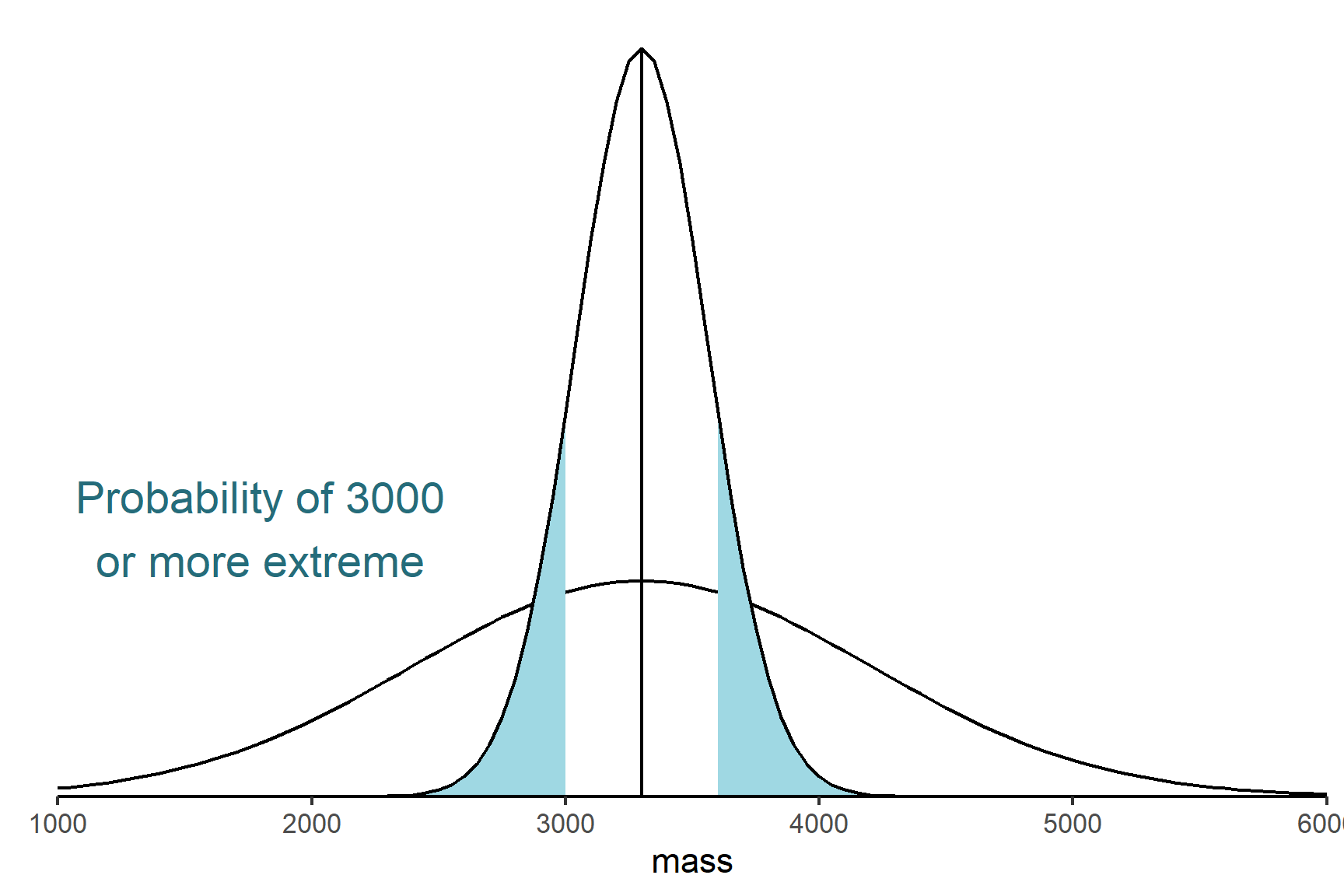

- Set up the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is what we expect to happen if nothing interesting is happening. In this case, that there is no effect of maternal poverty on birth weight, i.e., the mean of a sample of babies born into poverty is equal to the national average (Figure 9.2). This is written as \(H_0: \bar{x} = 3300\). The alternative hypothesis is that the sample mean is not equal to the national average. This is written as \(H_1: \bar{x} \neq 3300\).

- Design an experiment that generates data to test the null hypothesis1. We take a sample of \(n = 12\) women who live in poverty and determine the mean birth weight of their babies. We calculate \(\bar{x} = 3000 g\). This is lower than the national average but might we get a sample like that even if the null hypothesis is true?

- Determine the probability (the p-value) of getting our experimental data, or more extreme data, if \(H_0\) is true.

- Decide whether to reject or not reject the \(H_0\) based on that probability. If the shaded area is less than 0.05 we reject the null hypothesis and conclude there is a difference in the birth weights between the two groups. If the shaded area is more than 0.05 we do not reject the null hypothesis.

In fact this is an observational study rather than a real experimental study. This means we can potential conclude birth weight differs in the two groups but we cannot say maternal poverty causes that difference.↩︎